Hanying Creole

History -

Old Hanying -

Hanying Creole -

Modern Hanying -

Life on Mars

Phonology -

Old Hanying -

Hanying Creole -

Orthography

Morphology -

Verbs -

Pronouns -

Nouns -

Reduplication -

Numbers -

Derivations

Syntax -

Sentence order -

Topic-comment -

Negation -

Yes/no questions -

Interrogatives -

NP order -

Copula -

Interjections -

Imperatives -

Conjunctions -

Possession -

Pivot -

Valence -

Locatives -

Time -

Ditransitives -

Serial verbs -

Speech -

Relativization -

Comparatives -

Conditionals -

Calendar -

Cities

Sample texts -

Diamond Sutra -

Welcome to Mars -

Mars Exchange

Lexicon

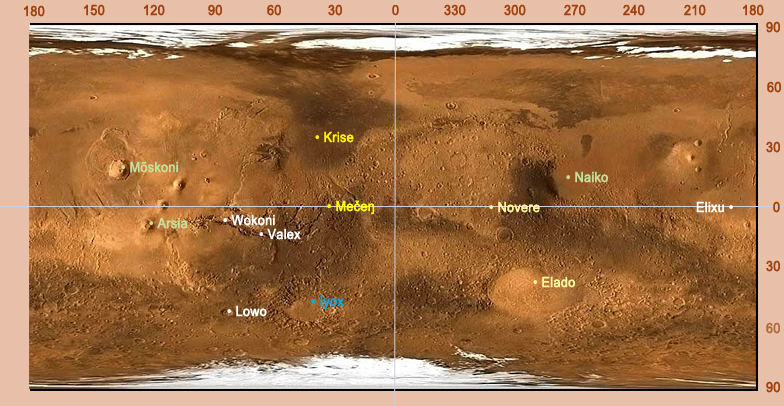

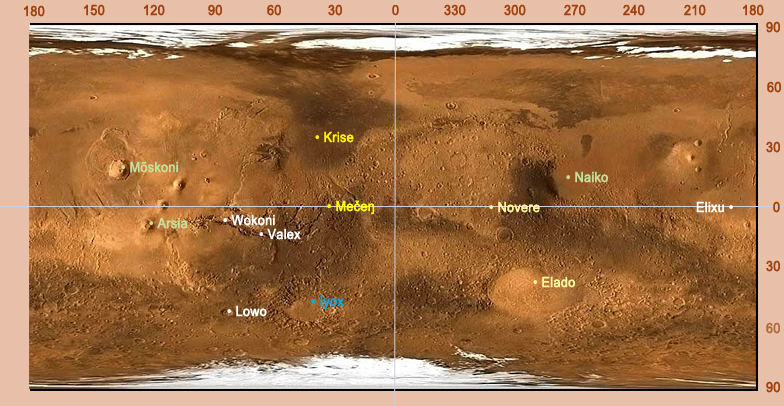

Note: The map shows the (surviving) settlements of Mars circa 2200. Colonies are color-coded by language: white = Hanying, bright yellow = Mandarin, light yellow = Portunhol, blue = Swahili, light green = Marindi.

—Mark Rosenfelder, Jan. 2019

Hanying is the language of Areopolis and the dominant language of Mars. As in the last three thousand years Mars has overtaken Earth in economic and cultural power within the Douane, it can be said to be the most prestigious language in the solar system, and a leading language of the Incatena, in second place culturally only to Sihorian Franca.

For the Incatena language, see Modern Hanying. This page covers the earliest stage of the language, Old Hanying, and the stable Hanying Creole of about 2200.

The settlement of Mars dates to the late 21C, just before the Collapse. At that time, Europe and Russia focused their attention on the Moon, while the US, China, India, and Japan sent colonists to Mars.

During the Collapse, the few thousand colonists survived, barely, with little support from Earth. The colonists from the founding nations were thrown together, and a pidgin developed, called Hanyiŋ (from Hàn ‘Chinese’ + Yīng ‘English’).

The phonology is a compromise between English and Chinese. The multiple fricatives of Mandarin were merged to x / č / ts; tone was lost. English consonant clusters were simplified (though single unvoiced stops were allowed at the end of words); the th sounds were lost.

There were far more Chinese than American colonists, so the lexicon skews Mandarin. However, as a contemporary report says, “the Americans have more trouble learning Chinese, so important words are from English.” That includes numbers, pronouns, conjunctions, quantifiers, grammatical particles, and the word no. Technological words used internationally are usually English, unless Mandarin had a shorter word— e.g. dyen for ‘electricity’.

A scattering of words derives from Hindī, e.g. wala ‘person’. Many relate to the family and domestic work, as in the Hanying-speaking cities child care and education were often done by Hindī speakers. (Other colonies were Indian-run, but spoke Indian-English pidgins, not Hanying.)

Linguists call this stage Old Hanying (OH). Citations from OH will be in blue, and are characteristic of around 2100. However, OH was not standardized, and different speakers and cities could have different vocabulary or syntax. Moreover, you could always improvise— if two speakers could get their message across, it was valid OH.

Though the name Hanying dates back to OH, many non-Chinese speakers learning it believed that they were learning Chinese, and called it that in their own languages. This caused confusion at the time, and makes the interpretation of sources difficult even today, as we’re not always sure what is meant if someone is described as speaking “Chinese”. (Amusingly, some Chinese speakers referred to Hanying as Yīngyǔ— English.)

After the Collapse, a very different set of nations prevailed on Earth. Brazil, Australia, and Afrika ya Mashariki were the leading powers. China and India were able to spring back faster than the former West.

Starting in the mid-22C, these nations greatly expanded the Martian colonies. National colonies were discouraged, which made each settlement a melting pot of languages. Though colonists continued to speak their own languages, their children needed a lingua franca. Inevitably, in Areopolis and the central colonies, they learned Hanying— but again adapted the phonology, and replaced as much as half of the lexicon.

The dominant language in this process was Brazilian Portuguese. Brazilians were not the majority of the new colonists, and records from the 22C show a good deal of lexical and phonological variation— there were varieties that were more Chinese, or more Portuguese, or more Spanish. But as the language standardized, it almost always moved in the direction of Portuguese.

This stage is known as Hanying Creole (HC). The stage of the language described here dates to about 2200. Each city really has its own dialect, but the standard is that of Areopolis (Wokoni), in the Valles Marineris.

Fairly frequently, an OH word was not replaced in all derivations. E.g. dawã ‘big 10,000’ preserves OH da ‘big’, replaced in HC with grã; and fãixen ‘good-body = health’ preserves xenti ‘body’, replaced in HC by kopu; sẽjo ‘neighbor’ is ‘same building’, though sem has been replaced with memu.

It’s also worth pointing out that Chinese or English words were often retained when they were short: e.g. smač vs. inteligente, joji vs. edifício, dyẽ vs. elétrico.

Over the next centuries, the pidgin became many people’s native language— in technical terms it was now a creole. It grew more complex and nuanced, and to some extent decreolized— that is, words were moved closer to their origins, if those languages were still widely spoken. In quite a few cases, this left doublets, an ‘international’ high-register word co-existing with a low-register word showing more phonetic simplification.

There was conflict over decreolization— some people still considered the creole as degraded or lazy. For awhile higher education was supposed to be conducted in other languages— but even here, in the common case where the teacher spoke HC, the class itself was run in HC. Besides, there was by no means consensus on what non-HC language to use: it was often felt that HC was “bad Portuguese”, but there was serious resistance to learning “real Portuguese”. In the end, Portuguese speakers were a minority, did not have a monopoly on power or prestige, and were unable to supplant HC as a high-register standard. (In a classroom that happily used HC, many students, and often the professor, could simply not have understood standard Portuguese.)

Some form of HC was spoken in nearly half of the Martian cities. The other major languages were:

- Marindi, an English-Hindi creole, which prevailed in some older colonies

- Mandarin, also found in older colonies

- Martian Portunhol, used in some newer cities— Portuguese influenced by Spanish

- Swahili, used in some newer cities

There were also many people who spoke one of the “Martian” languages, but used another language at home or at work, or simply maintained it in order to retain a connection to Earth. These languages included English, Tamil, Indonesian, Arabic, and Japanese. These held on for centuries, but by the fourth millennium no longer had native speakers.

With the long lifetimes characteristic of the Incatena, linguistic change slowed down, but significant sound changes and grammatical changes affected Hanying. There were also new borrowings and semantic changes. The end result is Modern Hanying (MH), a language which the original colonists would have trouble recognizing.

The other languages also survived, except for Martian Mandarin, as its cities adopted HC.

I will start with a fairly full description of Hanying Creole, with references back to OH. This will serve as a basis for the discussion of Modern Hanying. MH is described on a separate page.

Linguistic note: If you want to know more about pidgins and creoles, see the chapter in my Advanced Language Construction. Loreto Todd’s Pidgins and Creoles is a good introduction; and as ever, Thomason & Kaufman’s Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics is essential.

My friend the cartoonist Greg Peters, looking at a picture of the Martian landscape, noted that if you added a highway and a BBQ restaurant, it would look a lot like Texas. Many people agree; supposedly 200,000 people have signed up for a one-way trip.

In fact Mars is not like Texas. It is, in the OH/HC period, a hellhole. The atmosphere is unbreathable and nearly nil. It’s enough for pretty skies, but air pressure is ½% what it is on Earth. The Mars rover Curiosity, which landed near the equator, reported highs of 4° C in summer and lows of -88° C in winter. For reference, the equivalent values at Earth’s South Pole are -26° C and -63° C.

If that’s not enough, it’s highly radioactive. Earth’s magnetosphere shields us from solar and cosmic radiation (fuxe); Mars basically has none. (“Oh, we’ll have machines do everything.” Surprise, radiation kills machines too.)

There’s no life, no oil, and little water. You can use solar power, but dust storms can reduce incoming light by 99%. And that’s to say nothing of the problem of transportation: gravity wells are a bitch. It’s hard to get things down there, and harder yet to get things back.

For all these reasons, there was a rush to get human beings to the Mars by 2040, and then a generation passed with no further activity. But by the last decades of the 21st century, lunar settlement was well advanced, so there was experience in hydroponics (paudažia), underground construction, far more efficient fuels and engines, solar and nuclear power. C-carbon (kõsisu - graphene, nanotubes, and more exotic configurations) allowed strong but light construction— a boon since nearly all materials still had to be ferried to Mars.

There are signs of this stage in the lexicon. The word for the surface (byauli) was also the word for ‘wilderness’— it meant an open but hostile environment. The best protection against radiation and freezing cold was to build underground; this is reflected in the word for ‘building’, joji— etymologically ‘dig-site’. To be dãuli ‘down inside’ was to be ‘safe and comfortable’.

Related is the important difference between an exterior wall (muru) and an interior one (parej). A muru was thick and full of technology; breaching it was a serious threat to the colony. Similarly, a men ‘door’ might be simply an opening, while a waimen ‘gate to outside’ was complex and bulky, incorporating an airlock. And since openings in a muru had to be small, settlers called them viža ‘portholes’ rather than ‘windows’.

On Earth, historically, peasants were the lowest class, the people who scraped a living out of the soil and supported everyone else. On Mars, food was a high-tech industry. The paudalabo ‘hydroponics lab’ was the heart of the colony— a sprawling set of domes (natural light was essential) staffed by trained technicians, and it was said, “what the paudawalas want, they get.” You don’t mess with the technology that keeps the settlement alive. Even by 2200, there was nothing grown outside in the Martian soil.

Mars, and space in general, were not a libertarian paradise. Quite the opposite: they were highly cooperative environments, where basic sustenance was a communal operation and a human right. There was no homesteading and very little capitalism; creating a colony was more like building a space station. You can’t have inviolate houses and guns and an anti-state mentality when an an anti-social act doesn’t merely result in a murder or two, but genocide of the entire habitat. The life support inspector (baukan) was one of the most powerful people in any space colony, and had unlimited authority to poke around everyone’s living space.

There was no underclass: the poor couldn’t afford the trip, and you cannot have a class of people in your space colony who have nothing, and thus nothing to lose— they could do too much damage. And there was not much of a market, so no billionaires or class of rich people. Throughout this period Mars was far more egalitarian than any place on Earth, for the same reason that a university, an oil platform, or an Antarctic base is pretty egalitarian.

The Collapse on Earth delegitimized reactionary (fasi) ideologies definitively, much as Europe’s religious wars had made state churches unthinkable. As late as 2200, the main political division in the HC-speaking cities of Mars was between sosi ‘democratic socialists’ and monisa ‘Armonistas’, the even more communitarian ideology which originated on Brazil. There were people who wanted a larger market sector— the maketwala— but they had little power, and even they didn’t want to touch the communal institutions that provided life support, food, and health care.

Early setters were highly trained astronauts, scientists, technicians, or well-paid assistants— Mars wasn’t a place you could try out on a lark, or out of desperation. Things like police, courts, and armed forces developed slowly, and the lexicon reflects this. A policeman was hegwala ‘rule person’; the first courts were simply ‘hearing boards’, and kõseyu made do for both ‘board’ and ‘court’, wãkwala ‘chairman for ‘judge’. No Martian city had an army throughout our period, and the closest thing to a gun was a dyẽpau, a stun baton. (The last thing you want in a space habitat is a projectile weapon.)

On the other hand, scientific terminology was widespread, and even provided words for everyday life— e.g. mega ‘million’, fenče ‘molecule’ > ‘small amount’, otu ‘oxygen’ > ‘air (in a room)’, deuta ‘delta’ > ‘change’.

There were words for things— ‘lake’, ‘forest’, ‘horse’, ‘airplane’, ‘rain’, ‘king’— that didn’t exist on Mars. They were needed anyway, as metaphors or to understand Earth culture. But subsidary terms were minimal— there was no need to distinguish ‘shower, drizzle, rain, sleet, snow, storm, hurricane’ when there was no precipitation at all. Fẽbau was used to refer to Earth storms, but on Mars it meant a radiation or dust storm. Anyone on the surface carried a fumida ‘radiation meter’ and had to get to shelter during a fẽbau.

See also the section on the Martian calendar, as well as the introdution to Martian life in the sample texts.

Past 2500, life on Mars started to change, as the population grew into the millions, huge solar panels in space brought cheap energy, photonics revolutionzed AIs and enabled neurimplants, and asteroid and gas giant mining eased the materials shortage. Terraforming projects allowed the first in-ground agriculture and radiation diversion started to tame the outside, at least near the cities. For later developments, see the MH page.

Consonants

| Labial | Lab-dent | Dental | Alveolar | Velar | Uvular | Glottal |

| Plosive | p b | | t d | | k g | | |

| Fricative | | f | s | x ž | | | h |

| Affricate | | | | č j | | | |

| Nasals | m | | n | | ŋ | | |

| Liquids | | | l | | | | |

| Semivowel | w | | | y | | | |

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back |

| High | i | | u |

| Close | e | r | o |

| Low | | a | |

The overall system is a compromise between English and Chinese. There are no non-English or non-Chinese sounds.

X is pronounced [ʃ], English sh. This spelling was comfortable for both Mandarin and later Portuguese speakers.

Pronounce č as [tʃ], ž as [ʒ], j as [dʒ].

However, some sounds were pronounced differently based on ethnic background.

- English speakers pronounced p b etc. as [ph b]— that is, as a contrast in voice. Chinese speakers pronounced them [ph p]— that is, as a constrast in aspiration.

- Chinese speakers used [ü] where the pidgin had yu: e.g. nyuhai ‘girl’ = [nühaj].

- They pronounced h as [x], while English speakers used [h].

- Chinese speakers generally preserved tone; others did not.

The vowel e was pronounced [ə], while ei was [e].

The only consonants which can occur finally are n, ŋ, r, and the unvoiced stops p t k.

(Some words end in ts, e.b. naits ‘breast’. But this ts is a syllable of its own: [naj ts].)

Mandarin r was heard as ž, so r was never initial.

Under the influence of Brazilian Portuguese, HC added v, and tipped the scales toward h being [x]. Pairs like p b were now generally a voicing contrast with no aspiration.

All vowels could be nasalized. Tone was entirely lost.

Nasalization often distinguishes words, e.g. na ‘that’ vs. nã ‘not’, te ‘tea’ vs. tẽ ‘past tense’, ora ‘hour’ vs. õra ‘honor’. This was reinforced by a tendency to lax the non-nasalized vowels: te [tɛ], tẽ [tẽ].

Portuguese speakers missed the ei/e distinction; both came to be written e and pronounced [ɛ].

A final -n or -ŋ was usually nasalized, except in a one-syllable CVN word.

Consonant clusters appeared from borrowings.

Portuguese initial r and medial rr were heard as h, so HC continued to avoid initial r. But borrowings like prata, grã, kror extended its range.

Final consonants are not much looser than OH; but a surprising new one appeared: -č. This derived from -t in Portuguese, pronounced [tʃi] in the 20C, [tʃ] in the 21C.

When ts wasn’t lost due to lexical change, it simplified to s (tsau > sau ‘fuck’) or č (fents > fenče).

You may know that final -o in Portuguese is pronounced /u/. This has already been applied in its loans to HC (e.g. ferro > fexu). So HC -o really is /o/.

A general stress rule developed in HC: stress the first syllable of the root. Thus fubo, koni, wala, kãbai, wada. Compounds were stressed on the first root: Wokoni, dewala, aiwala, Haŋxo.

Spelling was at first haphazard. The language evolved for informal oral use— for writing, people used standard Chinese, English, Hindi, and so on.

Representing OH in novels, scripts, news reports, and so on, various approaches were used:

- Represent the words phonetically.

- Use the original orthography— English or pinyin.

- Use Chinese characters. (English words almost always had a clear Chinese translation.)

So for instance the OH sentence “You watched the girl” could be written

Yu det kan nyuhai.

You did kàn nǚhǎi.

你䙷看女孩。

With creolization, and adoption by Portuguese and Swahili speakers, the second and third options died out. However, there were often efforts to move the standard toward standard Portuguese. So you could write this sentence two ways:

Mi axa, fubo bi legau.

Mi acha, futbol bi legal.

I think Soccer is great.

This made little sense to native speakers and died out. However, in many cases the Portuguese word was retained as a high-register borrowing. E.g. the University of Areopolis was called the Wokoni Grãsku, but officially the Uvesidaj de Areópolis.

Special characters

In OH, x was frequently written sh or š or ś. X won out for its simplicity, and was reinforced by Portuguese spelling.

Similarly, č was written ch or č or ć or even tx.

The final spellings of č ž were simply c z, since these letters were not otherwise used. I’ve retained the diacritic as an aid to memory.

ŋ was often written ng, but the one-letter form was increasingly adopted as it was shorter.

Letter names

The names of the letters:

a be če de efe gi ha i je ke eli em en eñe eŋ o pe ku er esi te u ve wa exi ye žeč

(Q ku was still used as a symbol in mathematics, or in labelling things sequentially.)

Base words are not inflected, but can be modified by other words.

The verbal complex can be schematized as

pronoun modifiers verb

where the modifiers express tense and aspect.

Examples in OH and HC:

| I watch | mi kan | mi kan |

| I watched | mi det kan | mi tẽ kan |

| I will watch | mi xer kan | mi vo kan |

| I am watching | mi sit kan | mi sič kan |

| I was watching | mi det sit kan | mi tẽ sič kan |

| I stopped watching | mi kan le | mi le kan |

| I really watched | mi yese det kan | mi sĩ tẽ kan |

| I am watched | mi bai kan | mi bai kan |

| I was watched | mi det bai kan | mi tẽ bai kan |

Note the modifier replacements in HC, and the regularization of le’s position.

In HC, the first modifier is unstressed: vo KAN, but tẽ BAI kan. This set the stage for cliticization of the modifers in MH.

In HC, Chinese speakers were more apt to use the perfective le than past tense det; English speakers were the opposite. In HC tense became predominant, but it was common to leave it out in narratives— you told a story in the present tense. HC tẽ is from Pt. têm.

It’s not necessary to mark the past with tẽ, or the future with vo if there’s an explicit marker of time in the sentence:

Mi go Wokoni mĩtyẽ.

1s go Areopolis tomorrow

I’m going to Areopolis tomorrow.

Sič marks the progressive, showing that the action is ongoing, conceptualized as a process, or contrasted with a non-progressive action:

Yu det kambai, mi sit kan.

Mi sič kan wĩ se tẽ kãbai.

1s progr read when you past come

I was reading when you came.

As shown here, it’s not necessary to repeat tẽ twice in the sentence. If someone snatched your book away, however, it would be appropriate to protest:

Ai, mi sič kan!

interj/ 1s progr read

Hey, I was reading!

In OH, for Chinese speakers, le could be either perfective or perfect, and was even used as an intensive— a marker of importance. This was difficult for non-Chinese speakers. Some simply added it to all sentences (isn’t everything I say important?). But by HC, the meaning had settled down on a change of state.

Mi le xo Hanxo.

1s CoS speak Chinese-language

I speak Chinese now.

The modifier sĩ is emphatic, and is used when the speaker wants to emphasize that something is done—

Na livu mi sĩ kan!

that book 1s yes read

I really read that book!

OR, I finally finished that book!

or when the action has been doubted:

—Se nã tẽ go Wokoni.

2s not past go Areopolis

You didn’t go to Areopolis.

—Mi sĩ go!

1s yes go

Yes, I did!

Finally, bai creates passive sentences; this will be discussed below.

Personal Pronouns

The OH pronoun system had more or less the structure of Chinese, with the actual lexemes borrowed from English:

| | s | pl |

| 1 | mi | wi / yumi |

| 2 | yu | olayu |

| 3 | dei | oladei |

The ola- prefix, structurally paralleling Mandarin -men, comes from English “all”. The ola- versions were emphatic, only needed when the speaker wished to emphasize that multiple people were involved.

Yumi was used for “you and me”— that is, inclusive we— without being mandatory.

Most Hanying speakers saw no need to distinguish gender in pronouns. But Portuguese speakers disagreed. Their solution was to optionally add the person suffixes wala (m) and wali (f) to what had become de, forming dewala / dewali. It remained possible to refer to a single person as de if the gender was irrelevant or non-binary.

The ola- pronouns were lost in HC. However, Portuguese speakers imported se (from ’cê, earlier você), which became the informal 2s pronoun. Thus the HC system was:

| | s | pl |

| 1 | mi | wi / žumi |

| 2 | se / žu | žu |

| 3 | de | de |

| 3 m | dewala | |

| 3 f | dewali | |

In general pronouns must be included, if there is no other explicit subject.

HC speakers could be fussy about gender, and created variations on Hindī wala/wali:

| wala | person, male if constrasted with wali |

| wali | woman |

| walu | man |

| wale | person who is non-binary; also used when one wishes not to assume gender |

Any word with wala/wali could take these variants, including the pronouns.

No one really intended to create four-way distinction; it can be seen as a compromise between several approaches:

- Hindī speakers who had a m/f distinction, with masculine as the default

- Chinese speakers who found it natural to make no distinctions at all

- English and Portuguese speakers who expected to find m/f and also non-binary terms

Demonstratives

The demonstratives are dis “this/these” and na “that/those”.

Quantifiers / Indefinite pronouns

The quantifiers:

| | OH | HC |

| none | nan | nã |

| some | mo | ũ |

| all | ola | ola |

These, and the demonstratives, could be combined with wala ‘person’, xič ‘thing’, tãi ‘time’, li ‘place’: e.g.

| diswala | this (person) |

| naxič | that (thing) |

| nãtãi | never |

| nãli | nowhere |

| olali | everywhere |

| olawala | everyone |

| mowala | someone |

| moli | someplace |

Note that mo continued to be used to form ‘some’ compounds though it was replaced with ũ as a separate word.

The quantifiers could also be used with pronouns: nã wi ‘none of us’, ũ wi ‘some of us’, ola wi ‘all of us’. Note the change of meaning from OH olayu ‘you (plural)’ to ola žu ‘all of you’.

OH did not have any nominal morphology, including a plural.

In HC, the expression ũ koni ‘some cities’ could also be interpreted as a plural ‘cities’, though koni was still unmarked for number.

Ũ koni xo ĩduxo.

some city speak India-speech

Some cities speak Hindu.

(Ũ derives from uns ‘some’, not um ‘one’.)

In OH, reduplication could be used with various meanings. E.g.

Mi det mekfain hwo hwo.

1s past make-fine ship ship

Could mean:

I fixed all the ships.

I fixed each ship (i.e., I went one by one).

I fixed a bunch of ships.

I fixed the ships (intensive: I really did it).

You could also reduplicate the verb, with the meaning “I did it a little”. Two-syllable verbs usually lost the first syllable.

Mi det mekfain-fain hwo.

I worked on fixing the ships / I fixed them a little.

In HC reduplicating a noun X always means “a bunch of X”:

Mi tẽ mekafãi navu navu.

1s past fix ship ship

I fixed a bunch of ships.

Reduplicating an adjective has an intensive meaning:

Dewali meli meli.

3s-woman pretty pretty

She’s very beautiful.

The numbers from 0 to 10:

| | OH | HC | 10x |

| 0 | liŋ | siru | wãk |

| 1 | wange | wãk | des |

| 2 | tuge | tuk | oner |

| 3 | terige | tri | kilo |

| 4 | forge | for | wan |

| 5 | faige | faik | lak |

| 6 | sikige | sik | mega |

| 7 | sebege | sebe | kror |

| 8 | etige | ečik | iwã |

| 9 | nainge | nãik | giga |

| 10 | tenge | des | dawã |

In OH, Mandarin speakers maintained a simplified measure word system— e.g.

| teri ge daxiŋ | three planets |

| teri ben buk | three books |

| teri to nyoro | three cattle |

If you were counting abstractly, you just said wan, tu, teri, etc.

No one else followed them in this, and so the general classifier ge was used for everything, and came to be understood as part of the number. It was simplified to -k in HC.

There is a fairly complete set of powers of 10. A highly numerate society finds such concise terms useful. For naming any multiple of digit x 10x, from hundreds to tens of billions, it’s preferred to simply concatenate the digit and the power of 10:

| tukdes | 20 |

| trioner | 300 |

| forwan | 40,000 |

| faiklak | 500,000 |

| sikmega | 7 million |

| ečikgiga | 8 billion |

| nãikdawã | 90 billion |

For numbers below 100, you can just concatenate the ones digit:

| tukdes wãk | 21 |

| trides for | 34 |

| faikdes ečik | 58 |

For anything higher, you simply list the digits, but supply the highest power of ten.

| forwan tuk siru faik | 4205 |

| sikimega ečik tuk for siru tuk nãik | 6,824,029 |

The decimal point is pronounced dač:

| fordes dač siru faik | 40.05 |

The ordinal in OH was di, but this merged with da in HC: tudi > tukda ‘second’.

Basic arithmetic:

| jĩde tuk | -2 |

| fen tri | 1/3 |

| tuk fen tri | 2/3 |

| pai pau tuk | π2 |

| luč tuk | √2 |

| tuk ae tri meka faik | 2 + 3 = 5 |

| faik jĩde tri meka tuk | 5 – 3 = 2 |

| tuk bai tri meka sik | 2 × 3 = 6 |

| des fen faik meka tuk | 10 ÷ 5 = 2 |

| tuk pau tri meka ečik | 23 = 8 |

| trida luč ečik meka tuk | ∛8 = 2 |

| tuk ae tuk nã meka faik | 2 + 2 ≠ 5 |

Compound N+N verbs can be freely formed:

Haŋ Chinese + wala person > Haŋwala Chinese person

otu oxygen + toŋ tank > otutoŋ oxygen tank

wada water + navu ship > wadanavu ocean-going ship

Especially with Sinitic roots, a compound may use only the first syllable(s) of the components:

fuxe radiation + mida meter > fumida radiation gauge

taiko space + navu ship > taina spaceship

kilo thousand + mida meter > kimida kilometer

Some common derivations:

| -go | country | Haŋgo China |

| -wala | person | Haŋwala Chinese |

| -wali | woman | Haŋwali Chinese woman |

| -xo | language | Haŋxo Chinese language |

| fãi- | good to X | fãičifã edible; fãiai cute |

| bač- | bad to X | baččifã inedible |

| -da | adjectivizer> | konida urban |

| -žia | -ology | ãmožia biology |

| nã- | not, un- | nãsmat unintelligent |

| -ña | diminutive | mãuña kitty |

| da- | augmentative | dayenda big-eyed |

| -de | action, state | xikd teaching |

| -sõ | abstract N-izer | axasõ thought |

| -xič | stuff, things | taxič property |

| -kaža | place | gadakaža storehouse |

OH made heavy use of zero-derivation— that is, the same root was used for both noun and verb: žerdau ‘know, knowledge’; gobai ‘buy, purchase’; dou ‘wash, washing’.

Though this persisted in HC, it increasingly used -de or -sõ as the abstract nominalization: žedude, gobaide, dode.

Overall word order has consistently been SVO.

Dis mwali ai se.

This woman love 2s

This woman loves you.

However, a very common pattern for sentences is topic + comment, with the topic fronted:

Dis mwali, de ai se.

This woman / 3s love 2s

This woman, she loves you.

HC has no definite articles, but definiteness interacts with topic/comment.

If you’ve introduced something into the conversation, then refer to it later, the later reference is likely to be a topic:

Ta dis mwali bai guŋkaža. Mwali, de ai mi.

have this woman at work-place / woman / 3s love me

There’s this woman at work. This woman loves me.

By contrast, if you’re introducing the woman and commenting about her in one sentence, she can’t be a topic:

Mwali bai guŋkaža ai mi.

woman at office love me

A woman at work loves me.

The topic-comment construction is very frequent even or especially when the topic is not a constituent of the main sentence:

Yãme, yen tumač grã.

Yanmei / eye very big

Yanmei, her eyes are very big.

Čotyẽ, wi go bai alua.

autumn / we go to moon

Autumns, we go to the Moon.

Fubo, žu žedu žoga ke?

soccer / 2p know play Q

Soccer, do you know how to play it?

Though these sentences might introduce a particular topic, it must be relevant to the discourse. E.g. the first sentence might be uttered if we were talking about Yanmei, about classmates, about fictional characters, etc.

Negation is done with nã (OH no) before the verb:

Mwali nã ai se.

woman not love 2s

The woman doesn’t love you.

It appears before any modifiers:

Mwali nã tẽ ai se.

Woman not past love 2s

The woman didn’t love you.

If there’s another negative word in the sentence, you still include nã:

Mwali nã tẽ ai se nãtãi.

woman not past love 2s never

The woman never loved you.

Yes/no questions are formed with final ke (OH ma):

Mawali ai yu ma?

Mwali ai žu ke?

woman love 2s Q

Does the woman love you?

In OH, you responded yese or no. But in HC you repeat the verb: ai, ña (ai). If there’s a modifier, you respond with the modifier:

—Mwali tẽ ai žu ke?

woman past love 2s Q

Did the woman love you?

—Tẽ.

Past

Yes, she did.

In OH you could also use the Mandarin V-not-V expression:

Mawali ai no ai yu?

Woman love not love 2s

Does the woman love you?

This was misunderstood in HC, becoming an expression of doubt:

Mwali ai nã ai se.

Woman love not love 2s

The woman may or may not love you.

A negative question is straightforward:

Mwali nã tẽ ai se ke?

Woman not past love 2s Q

Didn’t the woman love you?

If you want to contradict the negative, you must say sĩ, optionally followed by the verb or modifier:

—Sĩ (tẽ)!

yes past

Yes, she did.

—Nã (tẽ)!

no past

No, she didn't.

The basic interrogatives:

| hu | kẽ | who |

| wat | wat | what |

| win | wĩ | when |

| wea | õji | where |

| watfor | wanwat | why |

| yuŋwat | yuŋwat | how |

| | kwau | which |

These are most often fronted:

Hu le kai dis vavu?

who CoS open this valve

Who opened this valve?

Õji wi go jĩtyẽ?

where 1p go today

Where are we going today?

Wat na xagwa tẽ faka?

what that idiot past break

What did that idiot break?

However, it’s correct to leave the interrogative in the logical place in the sentence:

Na xagwa tẽ faka wat?

that idiot past break what

What did that idiot break?

And in fact this is preferred if the interrogative element is in a subclause or a conjunction:

Jwedi tẽ gobũ diswat dewala kai wat?

building past explode because he open what

The building exploded because he opened what?

Pego bai Mariya ae kẽ?

walk at Mariya and who

You’re going out with Mariya and who?

See below for relative clauses— some but not all the interrogatives can be used for these.

NP order is consistently modifier-modified.

| tuk nuña | two girls |

| na nuña | that girl |

| fãi nuña | a good girl |

| deda nuña | his girl |

| Mariya da nuña | Maria’s girl |

| tumač fãi | very good |

The copula is bi, used with another noun:

Teha bi daxiŋ ke?

earth be planet Q

Is Earth a planet?

Existentials do not use bi; see below.

Adjectives could generally function as verbs:

Žu (nã) meli.

2p (not) pretty

You’re (not) beautiful.

Žu tẽ meli.

2p past pretty

You were beautiful.

Besides interrogative ke, there are several sentence-final particles. These are of Chinese origin, but proved so useful that they were adopted by everyone. Using them correctly was said to be a mark of being a native Martian.

In fact, many of the sample sentences in this grammatical sketch would sound wrong to a HC speaker, because they lack the particles. But as their meaning is pragmatic and thus dependent on the context of the utterance (as well as the relationship of the speakers), they can’t easily be applied to out-of-context sentences.

The commonest and subtlest is la. One usage is to soften a statement or imperative:

Gẽna mi la.

give 1s OK

Give it to me, huh?

Mi nã meivi kãbai la.

1s not can come OK

I’m afraid I can’t come.

Or it can offer reassurance:

Kloge nã vo gobũ la!

heat-exchange not future explode OK

Don’t worry, the heat exchanger isn’t going to explode.

It can be used to appeal to solidarity— a possible paraphrase might be “This is how I feel, please act in accordance with that.” E.g. this sentence might be offered as an explanation for why the speaker can’t go to a party:

Dami lau aiwala vo bi naču la.

sub-1s old spouse future be there OK

My ex-spouse is going to be there.

The closest American English equivalent is probably “OK”, which is how I’ve glossed it above. HC also has oke, which acts as an interjection and is better as a one-word response.

Wat emphasizes that something is, or should be, obvious:

Dis puda faka wat?

this computer break what

This computer is broken, don’t you know?

It’s also used with the opposite meaning, expressing incredulity:

Se nã tẽ kan livu wat?

2s not past watch book what

Shit, you didn’t read the book?

Ne introduces a new, contrastive topic:

Mariya geda, Tereza ne?

Mariya gay / Tereza PT

Mariya is gay; what about Tereza?

Ba is used to solicit agreement:

Se vo takoč bai towala ba?

1p future explain by boss PT

You’re going to explain everything to the boss, right?

This can be combined with la or wat:

Wi vo čuku distãi ba la?

We future leave now PT PT

We’re going to leave now, right?

Or you can add words representing laughter:

Se tumač laik dis nuña haha.

2s very like this girl haha

You really like this girl LOL.

Haha is a normal laugh; hehe is more restrained (a chuckle). Xixi represents a girlish or mischievous laugh.

In OH, English speakers could use lol the same way. Some Chinese speakers borrowed this as lou, but the Chinese laughs won out in HC. But the old word survived in xolo ‘say LOL’ = ‘laugh’.

The laugh words can be used freely as interjections, e.g. standalone or fronted:

Haha se tumač laik dis nuña.

haha 2s very like this girl

LOL, you really like this girl.

The other particles cannot be used alone (e.g. as the entirety of an utterance), except for wat. You’ll often hear Wat la in the sense “Yeah, of course” or “Well, duh.”

The equivalent of standalone “OK” is Sĩ la “Yeah, sure.”

The most common swear words are sau ‘fuck’, jẽta ‘damn’, gwe ‘devil’, jiba ‘cock’, ñobi ‘cunt’. All can be used as interjections, usually beginning a sentence. Note the common Gwe wat? “What the fuck?”

The first two are used as verbs:

Jẽta dami xikwala!

Damn sub-1s teacher

Damn my teacher!

As modifiers, they usually take da:

Mi vo kižu na sauda jiba.

1s future kill that fuck-sub cock

I’m gonna kill that fucking bastard.

The swear words come from Chinese— for Chinese speakers, only these had the requisite profanity. English swear words were adopted too, for their vividness, but by HC had softened into ordinary lexical items: fakap ‘fuck up’ = faka ‘break, go wrong’; xit ‘shit’ = xič ‘thing, stuff’.

The simplest imperative is the verb root: Kãbai! “Come!” Čifã! “Eat!”

Though you can form negative imperatives with just nã, it’s more common to say e.g.

Nã wan čifã na!

not want eat that

Don’t eat that!

This is a loan-translation of Mandarin bú yào ‘not want’.

Nomo is used when the order is to stop doing something: Nomo čifã! “Stop eating!”

To soften a command, you can add plis (Plis sič! “Please sit!”), or (as noted above) use la.

Another useful polite formula:

Tumač fãi, se nã xo xikwala mi faka de.

very good / 2s not say teacher 1s break 3s

It’d be good if you didn’t tell the teacher I broke it.

A first- or third-person imperative can be indicated by tone of voice (wi čifã! “Let’s eat!”), or more unambiguously by using one of the politeness strategies:

Wi nã wan xo naxič la.

We not want speak that.thing OK

We don’t want to talk about that.

You can use ae ‘and’ as in English:

| Mi ae žu | you and I |

| Mi xo Iŋxo ae Hanxo. | I speak English and Chinese. |

| Dewali meli ae smat. | She is beautiful and intelligent. |

But it’s more common to concatenate the alternatives, then add kaj ‘each’:

Mi xo Iŋxo Hanxo kaj.

1s speak English Chinese all

I speak English and Chinese.

Dewali meli smat kaj.

she beautiful smart all

She’s both beautiful and intelligent.

Similarly, rather than use o ‘or’, it’s common to list the alternatives and add ũ ‘one’:

Dewala xo Iŋxo Hanxo ũ, mi nã žedu kwau.

he speak English Chinese one / 1s not know which

He speaks English or Chinese, I don’t know which.

Possession is indicated with ta (OH yo).

Mi ta seu.

1s have phone

I have a phone.

Žu tẽ ta nak, žu nã le ta nãxič.

2p past have money / 2p not CoS have nothing

You used to have money, now you have nothing.

In OH, a possessive expression was a relative clause, e.g. mi da xoji ‘my phone’, nyuhai da yen ‘the girl’s eyes’. This sounded backwards to Portuguese speakers, who would often say seu da mi, yen da nuña. To avoid confusion, people settled on a new order:

| dami seu | da nuña yen |

| sub 1s phone | sub girl eye |

| My phone | The girl’s eyes |

For the singular pronouns, the possessive is written without a space: dami ‘my’, dase ‘your’, dade ‘his/her/its’. The OH equivalents were mida, yuda, deida.

Without a subject, the possessive is an existential:

Yo nyuhai bai men.

Ta nuña bai men.

have girl at door

There’s a girl at the door.

In OH there was a special negator mei for this, but in HC this was replaced by nã.

Mei yo nyuhai bai men.

Nã ta nuña bai men.

not have girl at door

There’s no girl at the door.

As in Mandarin, you could have a pivot construction— that is, the object of one clause becomes the subject of the next:

De wan mi go Wokoni.

3s want 1s go Areopolis

They want me to go to Areopolis.

Mi axa žu bi Haŋwala.

1s think 2p be China-person

I think you’re Chinese.

HC retained Mandarin’s laxness of valence. A normally transitive verb with just one argument would be interpreted as intransitive:

Mi tẽ do fitu.

1s past clean filter

I cleaned the filter.

Fitu tẽ do.

The filter was cleaned.

Na mekwala le faka puda.

that engineer CoS break computer

That engineer just broke the computer.

Dis puda le faka.

this computer CoS break

This computer was just broken.

A subject could be reinserted with bai. (This is probably from Mandarin bèi, but merged with the preposition bai from English by.)

Fitu tẽ do bai mi.

The filter was cleaned by me.

You could also place bai before the verb. This reinforced a passive interpretation, and also emphasized completion.

Fitu bai tẽ do.

filter by past clean

The filter got cleaned.

Dis puda bai tẽ faka.

this computer by past break

This computer got broken.

To form a causative, you use a word like meka ‘make, do’, in a pivot construction:

Towala tẽ meka mekwala do maxin.

boss past make engineer clean machine

The boss made the engineer clean the machine.

Dis xagwa vo meka maxin faka.

this idiot future make machine break

This idiot is going to make the machine break.

HC is very tolerant of what we can call applicatives— verbs that are semantically intransitive but which take an argument without a preposition: a measurement, a result, or even a type of action:

Obita tẽ voa tuk memida.

Orbital past fly two million-meter

The orbital flew 2000 km.

Mi vo kasa žu kižu!

1s future hunt 2p kill

I’m going to hunt you to death.

Dewali tẽ kohe xãda.

She past run home

She ran home.

Tomas le deč xnuf ke?

Tomas CoS dead drugs Q

Did Tomas die from drugs?

A locative expression is often no more than bai + NP. This will cover a good many cases where English feels the need for a particular preposition.

| bai taiko | in space |

| bai meza | on the table |

| bai koni | in the city |

| bai isku | at school |

| bai moči | in the mountains |

For more specificity you add a postposition:

| bai meza xamẽ | under the table |

| bai meza yomẽ | to the right of the table |

| bai meza byaumẽ | on top of the table |

The common meaning ‘out of’ can be expressed this way— bai koni waimẽ— but wai developed into an alternative or contrast to bai:

| wai koni | outside the city |

| wai meza | off the table |

| wai moči | out of the mountains |

| wai isku | out of school, away from school |

Locatives can be fairly freely placed within a sentence, but the commonest positions are at the front or back.

Wi vo go bai Wokoni.

we future go by Areopolis

We’re going to go to Areopolis.

Bai Wokoni ta mwitu meli nuña.

in Areopolis have many beautiful girl

In Areopolis there are many beautiful girls.

In formal registers, there’s a preposition de ‘of’:

| Nasõ de Brazu | the nation of Brazil |

| Taxič de Koni | property of the city |

Colloquially, these would be Brazu Nasõ, koni taxič.

Location in time is expressed with bai: bai yewã ‘at night’; bai verõ ‘during the summer’, bai maña ‘in the morning’.

The time can be the topic, in which case it may take a frequentative sense (“every X”):

Maña, mi weka gweda teŋ to.

Morning / 1s wake devil-sub pain head

Every morning I’d wake up with a damned headache.

Lacking great prepositional reserves, HC uses the future tense particle vo for future time, and tẽ for past time:

| tẽ verõ | since summer |

| tẽ juŋjia | after noon |

| vo duntyẽ | until winter |

| vo juŋjia | before noon |

To express duration, you can use ola ‘all’: ola jia ‘for the whole day’, ola ñen ‘for a year’.

HC doesn’t mind adding extra objects. In dative expressions, the indirect object normally comes first:

Mariya tẽ gẽna dewala liu.

Mariya past give he gift

Mariya gave him a present.

The indirect object can be backed, especially if the expression is long; in this case it’s preceded by bai:

Mariya tẽ gẽna liu bai dade pita.

Mariya past give gift at sub-3s father

Mariya gave a present to her father.

Either object can be passivized:

Liu bai tẽ gẽna (dewala) (bai Mariya).

gift by past give (he) (by Mariya)

The present was given (to him) (by Mariya).

Dewala bai tẽ gẽna (liu) (bai Mariya).

he by past give (gift) (by Mariya)

He was given it (the present) (by Mariya).

Similarly, verbs of naming or appointing can take two objects:

Mapita tẽ xama dewali Xaume.

parent past call she Xiaomei

Her parents called her Xiaomei.

Can you have multiple verbs in a row? What do you think? Of course you can.

Mi wan paka fãi čau murge.

1s want cook good stir.fry chicken

I want to cook a good chicken stir-fry.

You can get kind of crazy with it:

Se axa nomo guŋ xe na livu ke?

2s think stop work write that book Q

Are you thinking of stopping work on writing that book?

A useful subclass is resultatives: a sequence of verbs that gives the action and the result.

Baŋwala tẽ xuč kižu olaxo da.

gangster past shoot kill squeal sub

The gangster shot the informer dead.

If you need to change subjects, you just add them in, forming a pivot construction:

Mi wan se paka.

1s want 2s cook

I want you to cook.

There’s no special marker of reported speech, except for a dash in writing. (Quotation marks are not used in writing HC.)

Mariya tẽ xo —Mi vo čaŋai, dan nã bai žu.

Mariya past say / 1s future marry / but not at you

Mariya said, “I’m getting married, but not to you.”

To change this to reported speech, you just leave out the dash and correct the pronouns (but not the tenses).

Mariya tẽ xo de vo čaŋai, dan nã bai mi.

Mariya past say 3s future marry / but not at 1s

Mariya said she was getting married, but not to me.

Statement of belief work the same way.

Wi axa Wokoni Grãsku nubwan isku wai Dwana.

We think Areopolis University most school out Douane

We think the University of Areopolis is the best school in the Douane.

Unlike English, relative clauses normally go before the noun. The subordinator is da:

| Mi tẽ čifã ñoro. | → mi tẽ čifã da ñoro |

| 1s past eat beef | 1s past eat sub beef |

| I ate beef. | the beef I ate |

| |

| Mwali ai žu. | → ai žu da mwali |

| woman love 2p | love 2p sub woman |

With ambitransitive verbs, this construction can lead to ambiguities.

tẽ faka da maxin

past break sub machine

the machine that broke

OR, the machine that broke things

Context usually makes things clear, but if not, you can include indefinite pronouns, or use passive bai:

bai tẽ faka da maxin

by 3s past break sub machine

the machine that broke

tẽ faka xič da maxin

past break thing sub machine

the machine that broke things

If the relative clause is particularly long, it can be moved after the noun:

Mwali mi ai da ae mi čaŋai da

girl 1s love sub and 1s marry sub

The girl that I loved and that I married

You can leave out the main noun, in which case it’s taken as a vague “people” or “things”:

| mi tẽ bai da ñoro | → mi tẽ bai da |

| 1s past buy sub beef |

| the beef I bought | the things I bought

|

| |

| wi ai da wali | → wi ai da |

| 1p love sub person |

| The people we love | the ones we love |

In context, these might have definite reference. E.g. we already saw

Baŋwala tẽ xuč deč olaxo da.

gangster past shoot dead squeal sub

The gangster shot the informer dead.

Olaxo da is literally “(the one) who informs.” As we’re referring to a specific event, this must be a specific informer too.

In OH adjectives normally were subordinated: fain da nyuhai “girl who is fine” = “fine girl”. In MH this was lost. However, a few adjectives got the -da permanently attached.

A relative clause may be used often enough that it was largely lexicalized, and seen more as a modifier. In this case the words are hyphenated: nã-nume-da ‘that can’t be numbered’ = ‘countless’; mi-ai-da ‘that we love’ = ‘beloved’.

Possession was also marked with da; thus mawali da faŋ “the woman’s house”. But as noted, this confused Portuguese speakers, and MH settled on da mwali kaža.

Locatives can be subordinated with õji, time expressions with wĩ:

Olaxič le faka wĩ se čuku.

everything CoS break when 2s leave

Everything fell apart when you left.

Wi nã žedu õji wi bi ae õji wi go.

1p not know where we be and where we go

We don’t know where we are nor where we’re going.

Comparatives use the formula X wai Y .

Yãme wai Mariya meli.

Yanmei out Mariya beautiful

Yanmei is more beautiful than Mariya.

Olawai, Teha wai Woxẽ nã wača.

environment / Earth out Mars not dangerous

Earth’s environment is less dangerous than Mars’s.

In OH you used bi, from Mandarin bǐ, sometimes replaced with the all-purpose bai. But when wai was established contrasting with bai, it was seen as more appropriate.

Superlatives use the formula nubwan — etymologically ‘number one’. The comparison class can be given with wai.

Yãme nubwan meli.

Yanmei most beautiful

Yanmei is the most beautiful.

Yãme nubwan meli wai nuña.

Yanmei most beautiful out girl

Yanmei is the most beautiful of the girls.

In OH, an if clause could be formed just with concatenation:

Wi sumat, wi xer žu bai xyaoxiŋ.

Wi smat, wi vo moha bai xauxĩ.

1p smart / 1p future reside at asteroid

If we were smart, we’d go live in the asteroid belt.

This was still possible in HC, but it was preferred to mark the consequence (not the condition) with kažu, which derives from Portuguese neste caso ‘in that case’:

Dami dadu deč le, kažu mi ta kahu.

sub-1s pat.grandfather dead CoS / then 1s have car

If my paternal grandfather died, then I’d have a car.

There is no conditional tense, and the condition is in whatever tense would be used for an indicative sentence. Compare the deductive sentence:

Mi smat, entõ nã vo bai ãguka.

1s smart / therefore not future passive scam

I’m smart, so I won’t get scammed.

Timekeeping becomes more complicated when you have multiple planets and moons.

It’s easy on the Moon: the “day” is one month, so people just keep Earth time. Whether the sun is shining or not has little impact in the half-subterranean colonies.

In the time of HC, Martian colonies were mostly underground, to shield settlers from radiation. But there was every reason to orient life around the solar day: illumination, outside work, better temperatures. So the jia was a Martian day (24 h 39.5 m, in Earth terms or 1.027 Earth days). An Earth day was a dijia.

Hours that were not quite 1/24 of the day would be awkward, so an ora was 1/24 of the Martian day— about 61.6 Earth minutes.

The segõ (second) was too entrenched as a scientific term to mess with. So people just dealt with an ora being about 3699 seconds.

It would have been quixotic, however, to use Martian years. So the ñen was an Earth year; for tracking Martian seasons or the Martian orbit, you used the woñen or Martian year: 686.98 Earth days, 668.60 Mars days.

So far so good; what do you do with the months (mex)? The convention was to start a new month when the Earth month changed, but number them by Mars days. This meant that the lengths of the months were no longer fixed, but everyone had computers and it was not much more confusing than the fact that, for us, “one month” can be 28, 30, or 31 days.

This meant that (say) 14 January did not quite align between Earth and Mars time, and towards the end of the month the date was usually different on Mars.

Though the Martian prime meridian has been defined (since 1830) within Meridiani Planum, Martian standard time (WPT = Woxẽ Padrõ Tãi) is that of 300° W, two hours different— the closest meridian to Areopolis, located in the Valles Marineris (Valex). As on Earth, each city has its own time zone.

For historical purposes, you use the date where something happened. E.g. if you were born in Chennai on March 26, 2152, your birthday is March 26 on whatever planet you live.

For legal or scientific purposes, dates can be specified as wotãi “Martian time” or ditãi “Earth time”. Unless further specified, these meant WPT or UTC respectively.

Following Chinese convention, months are numbered, not named: Wãk mex = January, etc.

Weeks (smana) are local, based on the Martian day. As a corollary, the day of the week rarely matches on Earth and Mars— another thing your computer will tell you if you need to know.

For some religions the Earth day is particularly important. Most Muslims define juma, the weekly holy day, based on Mecca time, while orthodox Jews define sabadu based on Jerusalem time.

For reference, the major cities of Mars, and their major languages as of 2200:

| Areopolis | Wokoni | Hanying |

| Lowell | Lowo | Hanying |

| Valles | Valex | Hanying |

| Elisiograd | Elixu | Hanying |

| Meicheng | Mečeŋ | Mandarin |

| Helladópolis | Elado | Martian Portunhol |

| Nuevos Aires | Novere | Martian Portunhol | |

| Iyos | Iyox | Swahili |

| Mons Colony | Mõskoni | Marindi |

| Naya Kolkata | Naiko | Marindi |

OH from the late 21st century is not well documented—if it was written at all, it was in the form of text messages which were not preserved. We have wordlists, a couple of phrasebooks, and snatches of dialog in popular media. (As noted above, speakers often normalized forms to English or Chinese, so a text which has hallmarks of OH may not be good evidence for how the language worked.)

The settlers were not on the whole religious, but the religious were well motivated to use the languages that people would understand; our best early OH texts are from religious sources. One such is a translation of the Diamond Sutra by one Wáng Líhuā, published in Elisiograd in 2105.

The English text is back-translated from the OH. If you’re curious about the original, I like Thich Nhat Hanh’s translation.

Tsuen Fojiŋ • Siki di kwai

diamond sutra / six ord part

The Diamond Sutra • Part 6

Xuputi xwo Fat —Xirtsun, bai kamyen, yo ženmin ma, dei meibi tiŋ dis xik, dei zhende xinren?

Subhūti say Buddha / (World-lord), in future / have people Q / they maybe hear this teach / they true believe

Xirtsun represents Mandarin shìzūn and did not catch on in general.

Subhūti said to the Buddha, “Lord, will there be people who, hearing these teachings, have real faith in them?”

Fat xwo —No wan xwo na.

Buddha say / not want talk that

The Buddha said, “Don’t talk that way.

Mi det le fai oner nyen, xer yo ženmin, dei dudat gwei, dei tiŋ dis xik, zhende xinren bai dei.

1s dead perf five hundred year / future have people / they obey rule / they hear this teach / really believe in they

This line shows the typical sentence structure of OH: short sentences unlinked by any explicit connectives.

Five hundred years after my death, there will be those who observe the rules, who hear these words and have faith in them.

Dis ženmin pudaun juŋtse, no bai wan ge Fat, oa tu ge, oa teri for fai ge, dan bai Fat mei yo nube.

this people place seed / no at one MW Buddha / or two MW / or three four five MW / but at Buddha not have number

These people have sown seeds not before one Buddha, or two, or three, four, five; but before countless Buddhas.

Mowala fainget gei xin dis pava, jinjin wan ge sekon, dei xer yo le kwaile mei yo xye.

someone clear give heart this word / only one MW second / 3s future have perf happy no have measure

Anyone who gives clear confidence to these words, even for a moment, they will attain immeasurable happiness.”

Here’s the text in HC, showing off its relexification and increased grammaticalization. E.g. note how independent clauses in the longer sentences have become relative clauses.

Čuwẽ Fojiŋ • Sikda kwai

diamond sutra / six-sub part

Xuputi xo Buta —Donu, vo ta žẽči ke, tiŋ dis xiksõ da ae sĩ krer da?

Subhūti say Buddha / lord / future have people Q / hear this teaching sub and yes believe sub

Buta xo —Nã wan xo na žetu.

Buddha say / not want talk that way

Tẽ dami det, tẽ faik oner ñen, vo ta žẽči, dudač hegra da, tiŋ dis xiksõ da, ae sĩ krer da.

past sub-1s dead / past five hundred year / future have people / obey rule sub / hear this teaching sub / and yes believe sub

Dis žẽči por juŋče, nã bai wãk Buta, o tuk Buta, o tri for faik, dan bai nã-nume-da Buta.

this people place seed / no at one Buddha / or two Buddha/ or three four five / but at not-number-sub Buddha

Mowala fãigeč gẽna dade xin bai dis ci, memo ola wãk mẽtu, vo le yo nã-mida-da fližde.

someone clear give sub-3s heart at this word / same all one moment/ future CoS have no-measure-sub happiness

And here is the same text in Modern Hanying:

Læšuge Næsútar • Sekad næfəi

gen-diamond def-sutra / sixth def-part

Subuti ləzešó soʔ Boz, “Orad, ləyoméžai uyeʔ lesəd šeso ləyozíŋar jerə ləyokəyér kæš?

Subhūti 3-past-say to Buddha / honored / 3-fut-irr-exist pl-person this teaching 3-fut-hear-sub true 3-fut-believe-sub and

Boz ləzešó, “Wemo šol næžezu.

Buddha say / stop speak-imper thus

Te læmi ləyetso fəiʔ wenər uyen, ləyožái uyeʔ lesəd ufav ləyozíŋar ləyokəyér kæš.

after gen-1s death five hundred pl-year / 3-fut-exist pl-person this pl-word 3-fut-hear-sub true 3-fut-believe-sub and

Lesəd uyeʔ ləfór uduš, nagəl waʔ Boz deye, o toʔ Uguz, o təré fəgér fəiʔ wegəl, læn nanumər Uguz deye.

2this pl-person 3-put pl-seed / none one Buddha in.front / or two pl-Buddha / or 3 4 5 or / but countless pl-Buddha in.front

Wegəl faiɣet ləméɣemem lesəd ufav, so waʔ mezu, kædu ləyoméyež næmirəd fəežəd.”

some clear 3-irr-trust this pl-word / only one moment / then 3-fut-irr-get unmeasured happiness

This is part of a booklet issued to new settlers in the late 2100s. The booklet was multilingual, but the first language used was HC, a language which few settlers would know. (By that time the language was well documented, and some settlers might prepare themselves by studying it.) But of course even a government document aimed at foreigners has to be written by, and understandable to, the hosts— if nothing else, they need to tell at a glance whether they’re handing out the right document. And the sociolinguistic message— “this is the language you’d better be learning”— was not unwelcome.

This passage is a fair introduction to contemporary Martian conditions and values. Though the planet’s population was now nearly half a million, settlements were still precarious, depending both on high technology and on the hard work of the settlers. Though by this time settlers generally knew what they were getting into, it was felt necessary to emphasize that life in space was a community project where individual lawlessness was too dangerous to allow.

Bẽvĩdu bai Wokoni!

welcome by Areopolis

Welcome to Areopolis!

Wokoni, ye xama Areópolis da, bi nubwan lau koni bai Woxẽ.

Wokoni / also call Areópolis sub / be most old city by Mars

Wokoni, also called Areopolis, is the oldest colony on Mars.

Bai tẽ wãjwe bai Haŋgo ae Ameka, žũtu prože, tẽ ũ oner ñen.

by past found by China and America / together project / past one hundred year

It was founded as a joint project by China and the United States one hundred years ago.

Kaj Woxẽda koni bi lan-mem-da monisa komũde.

each Mars-sub city be run-self-sub Armonista community

Each Martian city is a self-governing Armonista community.

Ola mohawala skolye tokoni, ae ženida skolye koniwala guŋ ola ũ ñen bai Kõseyu de Ale.

all resident choose mayor / and random-sub by choose citzen work all one year at council of law

The second sentence is curious: it’s a pivot construction (around koniwala) with no explicit overall subject.

All residents elect a Mayor, and citizens are randomly selected to serve one year on the Legislative Council.

Kaj koniwala ta tri votu bai Wokoni ta da tri iče bai Palamẽtu de Woxẽ.

each citizen have three vote at Areopolis have sub three chair at Parliament of Mars

Both legislative bodies are named using the formal X de Y construction, often used in bureaucratese.

Each citizen has three votes for the three seats which Areopolis holds in the Parliament of Mars.

Žu leč votu wãk, tuk, o tri wanlan.

2p allow vote one two or three candidate

You can vote for one, two, or three candidates.

Kaj mohawala ae kãbaiwala ta jetu de ta otu, čifã, nãteŋ mohakaža, fãixenda gadade, viliki kaj.

each resident and visitor have right they have oxygen food safe residence health-sub care Vee-link each

As these benefits are seen as a package, the X X … kaj construction is better than one using the conjunction ae.

All residents and visitors have the right to oxygen, food, a safe place to live, health care, Vee access.

Gosõ xiksõ kaj nãkači.

movement education each free

Transportation and education are free.

Mohawala, nãxo ta visa de kãbai da, espar žuku komũde, guŋ o len, ae gada da koni bauvida.

resident / except have visa of visit sub / expect join community / work or study / and keep sub city support-life

Residents, except for those with a visitor visa, are expected to participate in the community, work or study, and maintain the city’s life support.

Waiwo kãbaiwala bixur kan bauvida da trenade.

off.planet visitor must see support-life sub training

Visitors from off-planet must attend life support training.

Da wi koni bi žuŋfaka mekade bai wača byauli bai fẽbau datumač friu, bačxusi či, ae mekadeč fuxe.

sub 1p city be easy-break construction by dangerous surface by storm extreme cold bad-breathe air and make-dead radiation

Here’s a pivot construction (around byauli) assisted by a passive in the second clause.

Our city is a fragile construction in a dangerous wilderness, ravaged by extreme cold, unbreathable air, and deadly radiation.

Dan moha ae krese bai komũde, gefãi grã.

but live and grow in community / reward great

Note the topic construction.

But the rewards of living and growing as a community are great.

This is a portion of my interactive exploration of AD 4901 Areopolis.

It features part of a conversation between Morgan, the Incatena Agent who’s the hero of my novel Against Peace and Freedom, and an old friend, financial analyst Antonia Chang-Nkruda.

It’s a chance to hear Morgan speaking their native language. Well, the ancestal form of their native language… Morgan spoke Modern Hanying, not Hanying Creole. Yes, this is very much like translating a James Bond novel into Old English. But it should be useful to compare the same passage to the MH version.

(In case there’s any confusion: the web page is written in the second person. “You” are the player, playing Morgan. Games and Vee sites address the reader formally as žu, not se.)

This is a good case study for the use of conversational particles.

Žu sit bai da Ãtoña meza.

2p sit by sub Antonia table

You sit down at Antonia’s table.

Žu ta kõta kači, entõ waño Qeŋda boŋmačli.

2p have account card / therefore order Qeng-sub slap-fish

You’re on an expense account, so you order the Qengese slamfish.

Dewali hiku, entõ waño jĩuji paka da xauñoro.

she rich / therefore order antimatter cook sub veal

She’s rich, so she orders the antimatter-cooked veal.

Bati yuŋ xau uji-jĩuji gobũde meka klo; nã wai mikrõda fãi, dan datumač danak.

oven use small matter-antimatter explosion make heat / not from microwave good / but extreme expensive

The oven uses a little matter/antimatter explosions to generate heat; it’s no better than microwaving but it’s frightfully expensive.

Ãtoña sohi žu. —Oi, Morgan. Se prese meme, olatãi žetu la.

Antonia smile 2p / hello Morgan / 2s seem dear / always way OK

Antonia smiles at you. “Hello, Morgan. You’re looking as darling as ever.”

—Xexe, Toña. Zul Ormãt ne, wat se žedu?

thanks Toña / Jules Orman topic / what 2s know

“Thank you, Toña. What do you know about Jules Ormant?”

Dewali xaumuh. —Se ola bijne. Ae ee ye dewala.

she pout / 2s all business / and well also he

She pouts. “You’re all business. And, well, so is he.

Dewala dagrã jãlide bai Geka, ta fen tri Novi Barat, ae možetu gãbe Paxu Pači bai Okura.

he huge standing at Exchange / have fraction three New Bharat / and somehow pal.with peace party by Okura

He’s a huge presence on the Exchange, he owns a third of New Bharat, and he’s carrying on somehow with the Okura Peace Party.”

Bi novide. —Bai Okura wat? Yuŋwat na? Bi kãina pornakwala?

be novelty / at Okura what / how that / be somewhat investor

This is news. "With Okura? How so? Is he an investor or something?”

—Bai ũ nak nali, dan wai na grã.

at some money there / but from that big

“He has some credits there, but it’s more than that. <

Okura tẽ lan Paxu Pači karvau tẽ tutri ñen, ae dewala bi kãbaiwala de õra.

Okura past manage peace party festival past two-three year / and he be visitor of honor

Okura organized a Peace Party festival here a couple years back, and he was the guest of honor.”

—Dan de bi wãkkrasiwala ba… dewala krer sĩ naxič ke?

but they be totalitarian-person PT / he believe yes that-stuff Q

“But they’re totalitarians... does he believe that stuff?”

—De make baixu pličikde disli, nãxo xau fãixo Kumari.

they make quiet politics here / except small praise Kumari

“They downplay the politics here, beyond a little praise of Kumari.

De meka prese kãina dausõ.

they make look somewhat religion

They present it as a kind of spirituality. <

Naxič sĩ fika bai mẽči, diswat nãwala nã por Ormãt na pava. Dewala žedu so krasi.

that-thing yes remain in mind / because no-one not put Ormant that word / he know only power

It stuck in my mind because nobody ever associates that word with Ormant. He’s all about power.

Meivi bi jẽde xič wãk liki oda.

maybe be real thing one link other

Maybe that’s the real link between them.”

—Xexe, Toña ba, naxič ĩtresa.

thanks / Toña PT / that-thing interesting

“Thank you, Toña, that’s interesting.”

—Mi espar se nã tẽ kãmbai bõba mi deta bai na tuk solo ba— dewali xwo, minda por dade manu bai da žu.

1s hope 2s not past visit pump me data by that two rogue PT / she say / mean-sub put sub-3s hand at sub 2p

“I hope you didn’t come by just to pump me for data on those two rogues," she says, putting her hand on yours meaningfully.

Kãmbai dami jojiña dis taji la… Mi ta ũ Ŋembe xnuf se nã krer da, ae mi tumač ai meka kan dami novi pele komo.

visit sub-1s home this afternoon OK / 1s have some Ngembe drugs 2s not believe sub / and 1s very love make see sub-1s new skin body-mod

"Come back to my place this afternoon... I have some Ngembe dust that you won’t believe, and I would adore to show off my new skin implants.”

First column is HC; second column is OH.

Etymologies: E English, M Mandarin, H Hindī, Pt Portuguese. Language omitted if it’s obvious, which it usually is (only M has tones; you know E; the rest is Pt). A slash separates HC / OH etymons.

If the OH is missing, that doesn’t mean the concept is inexpressible, only that it has no fixed lexeme. Just paraphrase in simpler terms; it’s what OH speakers did.

If you want a HC word that isn’t here, it is not entirely irresponsible to take the Portuguese root and adapt it to HC phonology. It isn’t guaranteed to be right, but Portuguese itself was widespread enough that you’re likely to be understood.

955 words

| a | — | letter A |

| ãbuge | hanbao | hamburger [Pt / hànbǎobāo] |

| ači | yixu | art [arte / yìshù] |

| ačiwala | yixuwala | artist |

| Afika | Feijo | Africa [África / Fēizhōu] |

| ãguka | dwolo | scam; fall for [Swahili anguka / piànjú] |

| ae | an | and, plus [E] |

| ai | ai | hey! oh! Ow! |

| ai | ai | love [ài] |

| aĩda | — | still, until now [ainda] |

| aiwala | aiwala | spouse, partner |

| aiwali | aiwali | wife (if aiwala is not used) |

| ajimira | — | admire; wonder at |

| ajimirasõ | — | admiration, wonder |

| ale | — | law [a lei] |

| aleda | — | legal, legislative |

| alewala | — | lawyer |

| Alla | Alahu | Allah (God for Muslims) [H] |

| alu | alu | aluminum [E] |

| Alengo | Degwo | Germany [alemã / Déguó] |

| Alenxo | Degxwo | German language |

| Alua | yučyu | moon (Luna) [a lua / Yuèqiú] |

| aluwala | aluwala | lunar settler |

| Ameka | Ameigwo | America [América / Měiguó] |

| Amekajo | Ameizhou | the Americas |

| amekwala | ameiwala | American |

| anime | anime | animation |

| ãmo | duŋwu | animal [animal / dòngwù] |

| ãmožia | duŋwuxwe | biology |

| arabe | alabo | Arab [Árabe / ālābó] |

| arabego | — | Arabia |

| arabexo | alaboxwo | Arabic language |

| aran | aran | rest, relax [H ārām] |

| aransõ | — | relaxation |

| arma | gan | gun [arma / E] |

| armoña | — | harmony, community (key Armonista concept) |

| Arsia | — | Arsia colony |

| asa | olayumao | wing [asa / ‘all feathers’] |

| asku | — | something disgusting [asco] |

| asu | lanse | blue [azul / lánsè] |

| atomu | yuents | atom [átomo / yuánzi] |

| auma | — | soul, spirit [alma] |

| avãu | feičwan | airplane, orbit-to-surface shuttle [avião / ‘fly ship’] |

| avi | nyo | bird [ave / niǎo] |

| axa | xyaŋ | think, consider; plan [achar / xiǎng] |

| Aža | Yajo | Asian [Ásia / Yàzhōu] |

| ba | ba | particle soliciting agreement [M] |

| bãbu | ju | bamboo [bambu / zhú] |

| bač | bat | bad [E] |

| baččifã | batčerfan | inedible [‘bad to eat’] |

| bači | bače | child [H baccā] |

| bačkan | batkan | ugly [‘bad to see’] |

| bačxusi | batxusi | unbreathable [‘bad to breathe’] |

| bag | bak | bug, insect [E] |

| bai | bai | at, by, in [by] |

| bai | bai | passive; X times [M bèi, merged with bai] |

| bãi | bai | brother [H bhāī] |

| bãida | baide | fraternal, brotherly |

| baiga | dupi | belly, abdomen [barriga / dùpí] |

| baise | baise | white [báisè] |

| baixiñu | — | kid [baixinho] |

| baixu | kwait | quiet; (HC) low, short [baixo / E]

meka baixu downplay, keep quiet |

| baŋ | baŋ | gang [bāng] |

| baŋwala | baŋwala | gangster, bandit |

| bati | batti | oven [H bhaṭṭī] |

| bau | bau | support, maintain [bǎo] |

| baukan | baukan | life support inspector |

| bauvida | bauxeng | life support |

| bastãč | tsugo | enough [bastante / zúgòu] |

| bastãwala | — | incrementalist [‘enoughist’] |

| basu | basu | arm [H bāzū] |

| bausina | baosin | news site, media source [bǎo ‘report’ + ‘scene’] |

| bauwala | baowala | reporter, journalist |

| be | — | letter B |

| bẽ | ben | sister [H behn] |

| beri | ber | berry [H ber, influenced by E] |

| besoru | pyaočuŋ | ‘beetle’, a flying taxi [besouro / piáochóng] |

| bẽvĩdu | fainkam | welcome [bemvindo / ‘good come’] |

| bi | bi | be [E] |

| — | bi | comparative (cf. wai) [bǐ] |

| bia | bier | beer |

| biblia | Yesubuk | Bible |

| biči | — | byte (unit of information) [international] |

| bijne | bijine | business |

| bixur | bixur | must, have to [bìxū reinterpreted as ‘be sure’] |

| bõba | beŋ | pump [bomba / bèng] |

| boŋ | boŋ | a ringing or pounding sound; pound, slap |

| bosa | — | lump, knob [bossa] |

| braitõ | — | Brighton music (atonal electronic dance music popularized in Brighton, England) |

| brãji | — | brand, trademark [Pt-ization of E] |

| Brazu | Baxi | Brazil |

| Brazuxo | Baxixwo | Portuguese |

| briga | fait | fight [brigar / E] |

| brigadu | — | gratitude, thanksgiving [obrigado] |

| bũda | pigu | butt, ass [bunda / pìgu] |

| Buta | Fat | Buddha [Pt / Cantonese] |

| Butadau | Fatjyao | Buddhism [‘Buddha’ + jiào (in HC dào)] |

| byauli | byaoli | the surface (of Mars or Luna); wilderness |

| byaumẽ | byaomien | (on the) surface, exterior [byǎomian] |

| byaupor | — | cover [‘top-put’] |

| čaŋ | čaŋ | long [cháng] |

| čaŋai | čaŋai | marry [‘long love’] |

| čaŋaide | — | marriage |

| čati | čati | chest (of body) [H chātī] |

| čau | čau | stir-fry [chǎo] |

| čawa | čawa | rice [H cāval] |

| če | — | letter Č or C |

| čedã | čedan | nonsense [chě dàn ‘pulling balls’] |

| čedãda | — | nonsensical |

| čego | čego | drive, go by car [‘car-go’] |

| či | (kuŋ)či | air, gas [kōngqì] |

| čibu | — | search exhaustively [E Kibo] |

| čida | — | airy, gaseous |

| čifã | čerfan | eat; food [chīfan] |

| čip | čip | electronic chip, component |

| čotyẽ | čyotyen | autumn [qiú] |

| čuku | čuko | exit, leave |

| čun | čun | group |

| čunkrasi | — | oligarchy |

| čuntyẽ | čuntyen | spring |

| čuwẽ | tsuen | diamond [zuàn] |

| da | da | subordinator [M de] |

| daaxa | — | important [‘big thought’] |

| dač | dat | point; decimal point [E dot] |

| dade | deida | his, hers, its |

| dadu | dada | paternal grandfather [H dādā] |

| Dafaka | Dafakap | the Collapse, late-21C social regression, a time of near desperation on Mars [‘great ruin’] |

| dagrã | dada | huge, enormous |

| daji | dadi | paternal grandmother [H dādī] |

| dami | mida | my |

| dan | dan | but |

| danak | danak | expensive [‘big money’] |

| danau | danao | genius [‘big brain’] |

| dañen | danyen | age, epoch, times [‘great year’] |

| dase | yuda | your (s.) |

| datumač | datumače | extreme, excessive [‘big too much’] |

| dãuli | daunli | safe inside; at home, at rest [‘down inside’] |

| daun | daun | down, downward |

| daxiŋ | daxiŋ | planet, world [dàxīng] |

| daxiŋda | — | planetary, global |

| dauda | daode | religious, spiritual [dào] |

| dausõ | dao | religion, spirituality |

| dãutãi | dauntan | bummer, mess [‘downtime’] |

| dawã | dawan | 10 billion [‘great’ + wã] |

| de | odei | they [E] |

| de | — | of [Pt de] |

| de | — | letter D |

| deč | det | dead; die (with CoS) [E] |

| dẽči | čir | tooth [dente / chǐ] |

| dedu | xojir | finger [dedo / shǒuzhǐ] |

| dewala | dei | he [de + wala] |

| dewali | dei | she [de + wali] |

| dejika | — | dedicate [Pt] |

| des | tenge | ten [Pt / E] |

| deta | deta | data, information [E] |

| deuta | derta | change; (math) delta |

| diču | disču | here [‘this place’] |

| dijia | dibaityẽ | Earth day [cf. Texa] |

| diñen | dinyen | Earth year |

| diora | diawer | Earth hour |

| dis | dis | this [E] |

| disli | disli | here |

| distãi | distain | now |

| diswala | diswala | this person, this one |

| diswat | — | because [‘this what’; cf. wanwat] |

| ditãi | ditain | Earth time |

| dixĩ | disxiŋ | sun (of the system we’re in) [‘this star’] |

| dixič | dixit | this thing, this one |

| do | dou | wash, clean [H dhonā] |

| dofu | doufu | tofu [dòufǔ] |

| dolum | doulun | sink, wash station [‘wash room’] |

| dona | — | lady (historic) [dona] |

| donu | gexya | lord (in historic contexts) [dono / géxià] |

| doñu | dou | bean [dòu + Pt. dim.] |

| dosi | kandi | candy [doce / H, E] |

| dudač | dudat | obey; follow (procedures) [‘do that’] |

| duntyẽ | duŋtyen | winter [dōngtiān] |

| duru | yiŋ | hard, rigid |

| dwana | — | the Douane [French] |

| dyẽ | dyen | electricity [diàn] |

| dyẽče | dyents | electron [diànzǐ] |

| dyẽda | — | electric |

| dyẽpau | dyengun | stun baton [‘electric stick’] |

| dyẽyen | dyenyen | camera [‘electric eye’] |