| October 2020 |

|

| Alejandro Jodorowsky & Moebius: The Incal | |

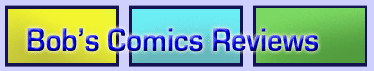

DiFool lives in a cité-puits, a city which starts in a hole in the surface and extends dizzyingly downwards— an architecture already explored in Moebius’s 1976 collaboration with Dan O’Bannon, “The Long Tomorrow”. At first Incal seems to be in the same vein: a far-future noir, set in the intersections of the “aristos” who inhabit the upper levels of the city, and the literal lower classes.

But it soon becomes far stranger. DiFool is attacked because he’s come into possession of the Incal, in the form of a small white metal device which, he’s told, is the key to the fate of the entire universe. At least, a lot of people think so: he's pursued by thugs of the rebel group Amok, birdlike aliens from another galaxy called Bergs, and the corrupt President of his own planet. He asks the Incal itself, and it starts talking to him. The start of this conversation is typical of the whole:

Incal: You finally decided to ask a question! That’s how I’m made: I never speak first...The Incal is right, of course: it’s something far more than a computer. And that's Jodorowsky’s move throughout: in each chapter the stakes get bigger, even higher powers get involved, the dangers are increased. The story becomes space opera— the entire galaxy is at stake— but John also acquires some powerful allies: the sisters Tanatah and Animah from the hollow earth, the world’s top assassin The Metabaron, Kill Tête-de-Chien (who really does have a dog’s head), the androgynous Solune, and John’s pet concrete bird Deepo, who has started to talk (and turns out to be smarter and braver than John) after John briefly concealed the Incal by making him eat it.

John: Extraordinary! A photonic miniaturized computer— now I understand everything!

Incal: You're wrong, Difool, and you’ve understood nothing!

Most of this wouldn't work without extraordinary graphics, but Moebius was at the top of his form here, creating one stunning vista after another. When Heavy Metal (the US version of Métal Hurlant, the magazine started by Moebius and a few others) appeared in the 1980s, it was a revelation to those of us used to US superhero and newspaper comics: amazing drawing skills, fancy coloring, an architectural eye for futuristic strangeness, and mature themes in several senses. Jack Kirby has a reputation for much of that in the US, but he doesn't hold a candle to Moebius, François Bourgeon, Enki Bilal, or J.C. Mézières.

You can see the same contrast if you watch The Fifth Element (partly designed by Moebius) and then the original Star Wars, with the sound off. The visuals in the the latter are good, but the French ones are amazing— and unashamedly over-the-top.

(US comics are drawn much better these days— cf. Planetary— probably in part because they had to compete with Heavy Metal.)

Now, the French superiority does not extend to story. Moebius on his own was no great writer. Jodorowsky (who is Chilean) is only a little better than superhero comics. He does bring to Incal a fevered spirituality, a mixture of Buddhism, psychiatry, and tarot. When this element is allowed to surface, it’s interesting. E.g. the Incal demonstrates to John— by cutting him into pieces— the four elements of his soul. But it tends to be forgotten for whole chapters.

The problem with space opera is that to make threats cosmic, they have to be invented and somewhat absurd. E.g the Technopriests have a plan to destroy the galaxy’s suns in order to exalt Darkness. OK, fine, that’s a bad thing and we should stop it. But there’s no attempt to explain it— even to show how the Technopriests themselves would benefit in any way. And once this plan is foiled, Jodorowsky is forced to escalate again and tell us that the Darkness is still there and has to be defeated by yet another plan.

What keeps the story from incoherence is its extraordinary vividness (most of this provided by Moebius), and the eternal rebelliousness of John. Sometimes he’s willing to be a hero; often he’s tired of it, and wants to go home, and return to his minor vices— whisky and robot prostitutes.

On the whole, the later books (of six) are less satisfying. The cosmic threats have become so huge and absurd that they become unreal, and the solutions are just as arbitrary. (And rather as in Philip Pullman’s epic, the last few pages, if read literally, totally destroy the story.) The best books are the first two, when John is still making new friends and enemies. Once the group is united, everyone but John starts to seem interchangeable.

I should probably add that European comics were something of a boyzone. The Incal is by no means the worst of these; it has a respectable woman warrior in Tanatah; an ongoing theme is that love and reconciliation are to be preferred to violence; and one of John's many defects is his very unenlightened libido. On the other hand, the other major female characters— Animah and the Berg Queen— spend most of their time naked or nearly so, and treating women as goddesses is not the same as treating them as fellow humans. A little more inscrutably, Jodorowsky seems to have a thing for androgyny. The ruler of the Galaxy is the Imperoratriz, with male and female halves joined back-to-back; both Solune and his archenemy the leader of the Technopriests seem to be perfectly androgynous.

Movie technology has advanced to the point that maybe the comic could be filmed. But it would probably be a disaster in the hands of an American director. They’d want it to be all grimdark, or make John more heroic, and either fade the spiritual elements into frivolity, or accentuate them into preaching. And they’d undoubtedly replace the last bit (where Darkness is confronted by... meditation) with a boss battle. Luc Besson could do it, only he kind of already did, with The Fifth Element.

There are a dozen or more prequels and sequels, with or without Moebius. I haven’t read any of them, though the plot summaries sound pretty bizarre. When you’ve already written an epic where the whole galaxy was threatened with destruction— and in your last pages God destroys and re-creates it— what can you possibly do next? One apocalypse is enough; two or more start to feel cheap.

| Pénélope Bagieu: Brazen | |

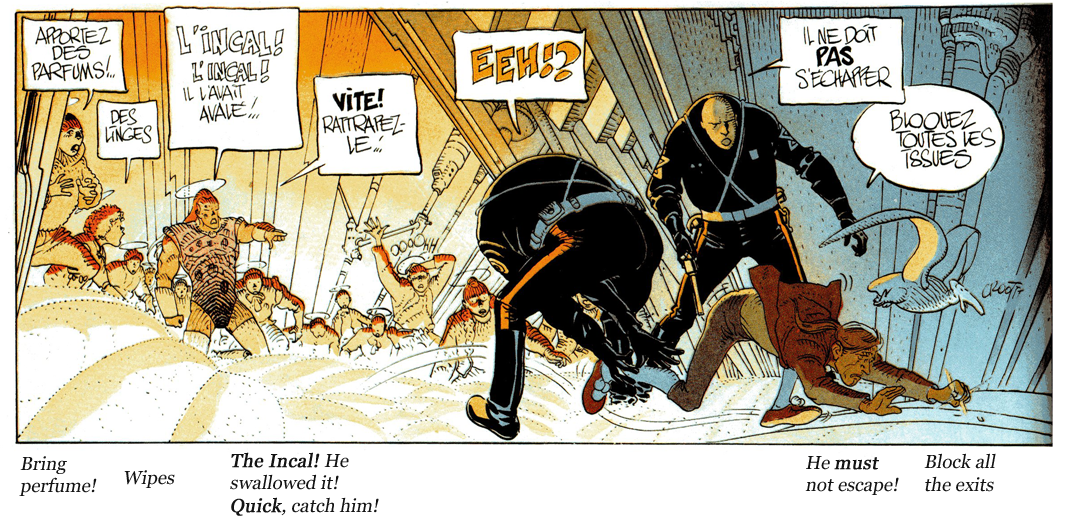

It's a series of delightful bios of women who defied convention in one way or another. It includes Josephine Baker, Christine Jorgensen, the Chinese empress Wǔ Zétiān, the Angolan queen Nzinga, a French bearded woman, the ancient Greek gynecologist Agnodike, the swimmer and swimsuit designer Annette Kellerman, the Apache warrior Lozen, Wizard of Oz actress Margaret Hamilton, and many more.

The stories are short, with cute yet adept drawings, and plenty of humorous asides. They're educational (I knew some of the women described, but not all), but not heavy-handed. People defying stupid conventions are almost always a good story.

A minor but key point: this sort of cartoony style is harder than it looks. Many a cartoonist learns to draw figures one way and their characters, even if well drawn, all look the same. Bagieu does a great job making each of her subjects distinctive.

| Tove Jansson: Moomin | |

The Moomins are best known from her novels, but she created a Moomin comic strip from 1954 to 1959. The books can be melancholy, but the comic is wholesome without ever descending into mere cuteness. It's divided into story arcs: the valley temporarily becomes a tropical jungle; a Martian spaceship lands there; Moominpappa brings the family to live in a lighthouse while he attempts to write a novel about the sea; Moomintroll falls in love with a diva; and so on. The comic has been handsomely reprinted by Drawn & Quarterly.

The family is generally confronted with some crisis or another (e.g. the diva story happens during a flood); everyone rushes around, there are quarrels and stupidities, eccentric outsiders come and go, but the Moomins' essential good nature always prevails. As E.M. Forster might say, the god of the Moomins is Muddle. Things never really go as planned-- e.g. Moomin's love affair goes badly (and annoys his regular girlfriend Snorkmaiden); during the jungle episode zookeepers imprison the Moomins as hippopotamuses; and at the lighthouse Moominpappa finds it impossible to write a single word. Even the main antagonistic figure, a small thieving furball named Stinky, ends up having to compliment them: "Indeed you are the most idiotic family I ever saw-- but you are at least living every minute of the day!"

A couple of graphics mechanics worth mentioning: one, the effective of blacks and half-tone, making the pages lively and attractive even in black and white; two, Jansson doesn’t care a fig for the conventions of daily comics: recaps and punchlines. She just treats each strip as one tier in a page, which makes them read very well in a collection.