| July 2016 |

|

| Brian Vaughan & Fiona Staples: Saga | |

Case in point: Saga. Vaughan wrote Y: The Last Man, which is high concept (“All the males disappear except one!”) and also pretty good. Saga is also high concept, though it takes a few more words to explain: Two worlds, a planet and its moon, are locked in an endless war which they have exported to the whole galaxy— forcing everyone to take sides. By accident, a woman and man from both sides fall in love and have a baby.

Case in point: Saga. Vaughan wrote Y: The Last Man, which is high concept (“All the males disappear except one!”) and also pretty good. Saga is also high concept, though it takes a few more words to explain: Two worlds, a planet and its moon, are locked in an endless war which they have exported to the whole galaxy— forcing everyone to take sides. By accident, a woman and man from both sides fall in love and have a baby.

In fact the story starts in mediās partī, when baby Hazel is born, which allows Vaughan to skip the romance (at first) and proceed right to the bit where the opposing sides try to kill them. Hazel has a large and impressive set of enemies: a mercenary named The Will, another mercenary named The Stalk, and an android with a TV screen for a head named Prince Robot IV. Oh, and some telepathic paparazzi, and later on a cell of terrorists.

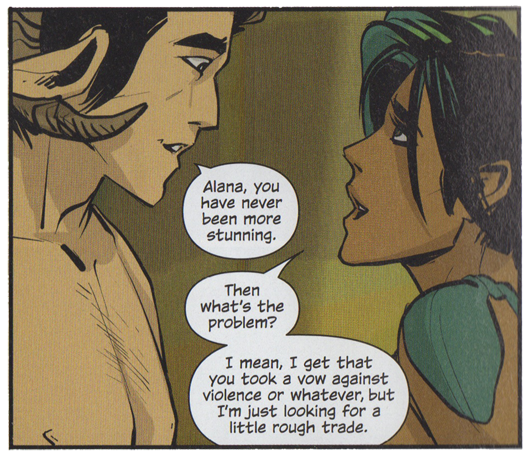

So, war and whimsy. It's not a bad combination, though occasionally it's a strange combination. Overall the series is fun. Hazel's parents, Marko and Alana, argue and flirt and get stressed out like normal people; they have in-law problems; they have a babysitter far cooler than they are (for one thing, she's a ghost). Their pursuers are all interesting, and turn out to have complicated lives and dilemmas of their own. Vaughan keeps things moving fast, but knows when to slow down for a more human moment, or for a joke. And every few issues there's an explosion of violence— usually offing a character we've come to like— and the family has to seek shelter elsewhere.

The worldbuilding, or galaxybuilding, is broad but fun. Marko’s people have horns, Alana’s have wings— Hazel has both. For some reason Marko and his people speak Esperanto. The Will is a badass with a companion animal who can detect lies; The Stalk is a female/spider hybrid and also has a romantic past with The Will. The TV sets that replace the androids' heads are usually blank, but sometimes they show something thematically relevant. Marko and Alana’s spaceship is organic, apparently a living and sentient tree.

Little of this would work without good art, and Staples consistently delivers. The fantasy landscapes, the organic ships, the weird aliens all work; just as important, the facial expressions are better than usual. (How many comics portray an argument with no real variation from <generic angry face>?)

Saga is one answer to the question, why world-build at all? why not just write historical fiction? A general antiwar message, or simply a story of lovers caught between opposing sides, is clearer when the antagonists are invented— a historical conflict brings too much baggage with it, too many assumptions about what’s the Right Side. Besides, of course, it’s fun to have TV-headed aliens. Also their hands turn into cannons.

I can’t think of any real negatives, though the story does get melodramatic at times… there’s a subplot in volume 4 about drugs, for instance, that’s like “What else can we throw at these people?” But then there’s a groundedness in the details of family life that saves it from the unreality of, say, grimdark.

| Alan Moore & Brian Bolland: Batman: The Killing Joke | |

Note: This review is not about the new movie, it’s about the comic. If you want something about the movie, Jamie Zawinski hates it.

Not gonna bury the lede: Killing Joke is pretty horrible. A lot of people think it’s a classic; what I think they’re responding to is its Grand-Guignol excess. A line from the linked article is key: the last director of the Grand-Guignol says, sadly, “We could never compete with Buchenwald.” You can’t out-horror the real world, and it’s unseemly to try.

Doing shocking things to cartoon characters shouldn’t be taken for sociopolitical insight.

Not gonna bury the lede: Killing Joke is pretty horrible. A lot of people think it’s a classic; what I think they’re responding to is its Grand-Guignol excess. A line from the linked article is key: the last director of the Grand-Guignol says, sadly, “We could never compete with Buchenwald.” You can’t out-horror the real world, and it’s unseemly to try.

Doing shocking things to cartoon characters shouldn’t be taken for sociopolitical insight.

The story: Joker attempts, one day, to prove his theory that “one bad day” will drive anyone to madness. His method is to shoot and paralyze Barbara Jordan, then use nude pictures of her to terrorize her father the commissioner.

Along the way we go over his own bad day— his origin story, which the original stories neglected to provide. He was a security guy at a chemical plant, and quit to become a bad comedian. Desperate to support his family, he agrees to take some crooks through the plant. Things go wrong, his wife dies suddenly, the thugs only get him into trouble, Batman is after him, and he jumps into a vat of chemicals that turn his skin white and his hair green and elongate his chin, as chemicals do. So he becomes an insane criminal mastermind.

Sigh. If Will Eisner had that idea, it’d be a 7-page gem, with the squishly little two-bit amateur safely drowned at the end, one more wannabe who wouldn’t listen to The Spirit’s warnings.

There’s nothing wrong with horror. If you want thrills and chills, go for it; there’s a huge pile of books and DVDs waiting for you. What annoys me about grimdark is that it pretends to Teach You A Thing Or Two, and doesn’t. It’s that over-intense guy who is a little too interested in Nazis and conspiracy theories and sex crimes, a chair-bound geek sneering that those other chair-bound geeks don’t understand human depravity as he does.

As a theory of psychopathy, The Killing Joke sucks. Horrible things happen to people all the time— it doesn't make them insane, criminals, or insane criminals. It may give them post-traumatic stress disorder, which is no joke, but is also no Joker. And your actual psychopaths are not generally pushed over the edge by the world mistreating them; they’re more likely to have a long, long history of doing disturbing things. Minor mental illness is all around you, messing people up but not making them into villains, much less supervillains. Major mental illness mostly makes people dysfunctional; they're sad, not charismatic.

As for crime, well, the story is not even trying to be insightful. The idea of someone helping thugs for specious reasons is believable, but as depicted, the proto-Joker is such a dweeb that a real criminal would be an idiot to take him along on any job. And there is zero explanation for how Mr. Chemical Accident was able to lead a criminal organization.

And as a superhero fantasy, it’s just irreparably nasty-minded. Moore himself has admitted that the treatment of Batgirl was a mistake. I can hardly be harsher about it than to point out that Frank Miller, in Sin City, gives women far more respect and agency. It's not just that Moore does something to Batgirl that he'd never do to Batman; it's that it's just a side event in the story. She doesn’t even have a story here; she’s something bad that happens to Jim Gordon, and he's just something bad that happens to Batman. Inventing a wife for proto-Joker and then disposing of her is more of the same.

Grimdark may have been refreshing in 1986, but grimdark does not improve with repetition. When a masterful creator decides to brutalize Batgirl, then everyone else thinks they need to be more brutal. The villains have to do ever more vile things, Batman must be more brooding, Gotham more lightless. But a literature of shock, referring chiefly to itself and not to anything in the world, is just as campy as 1960s Batman, and far less fun.

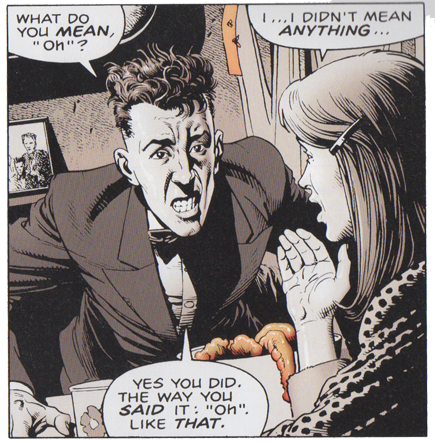

Beyond all that, I think the book misses the character of both Batman and the Joker. For instance, Batman scours the city to find where Joker’s taken the Commissioner… finally a thug hands him a note from the Joker giving his location. Seriously, Alan? The man’s a detective, let him figure something out.

As for the Joker, he should ideally be funny, and grandiose. Moore's Joker has a poor patter and really, the show he gives the Commissioner is lame. (If you're not sure about that, recall: he was there when Barbara was shot; taking pictures doesn’t add anything worse than that.)

The irony is, you can take pretty much the exact ideas and themes of these book, remix them, and get a pretty good graphic novel: bald-pated Grant Morrison & Dave McKean’s Batman: Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth (1989).

The story there is more or less that of the video game: the inmates have taken over the asylum (again!) and insist that Batman comes and confronts them all, while we're also told the story of Amadeus Arkham, founder of the asylum as well as one of its first patients. There's no nonsense about Batgirl and no attempt to give the villains backstories. It's just a long dark night of the soul for Batman— some fights, some taunts, some misguided psychologists, some reminders that on some level he’s a mixed-up bastard just like these crazy folks.

Plus, the story and art are feverishly insane, or try to be. This doesn’t always work, but it does here— we can buy some of the raving because Morrison buys it himself. Moore is way too analytic and rational to create a convincing crazy person: his eccentrics simply operate according to a different but still strict logic of their own. Morrison's view of Batman here is a little unorthodox (“This Batman is a frightened, threatened boy who has made himself terrible at the cost of his own humanity. He is completely incapable of any kind of sexual relationship. He has made himself hard and domineering in order that he might never be hurt or abandoned again.”), but it’s the kind of rethinking you need to do with genre material to make it live again.

Though, the page where Batman enters the Asylum and hears crazy murmurs turns out, in the script, to all be quotations from other literature. And that's the thing with grimdark: it's a comment about literature. So you don't make it good by making it more brutal… though you might do so by making it more literate.